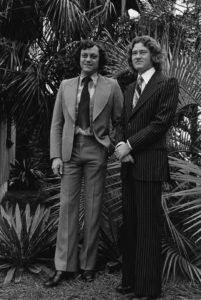

Frank Fenter and Phil Walden (Photo by Herb Kossover)

After tremendous success in the 1960s as the booking agent and manager of soul artists like Otis Redding, Percy Sledge, and Sam and Dave, Phil Walden turned his creative energies to founding a record label at the end of the decade to house his stable of talent. Walden’s plans also included the building of a local studio – complete with a session band to rival those in Muscle Shoals or Memphis – to record these artists. Named for their shared astrological sign, Phil Walden and Jerry Wexler (Atlantic Records) formed Capricorn Records as a subsidiary of Atlantic. Walden’s charisma and booking knowledge, paired with the business acumen and savvy ear of co-founder Frank Fenter (himself an import from Atlantic’s London office), spawned early and widespread success for the fledgling label that grew to influence the tastes of a nation as it brought southern soul and rock and roll to the masses.

Otis Redding

Phil Walden had been booking and acting as manager for black R&B acts on the fraternity circuit since his days at Macon’s Mercer University in the early 1960s. Through the decade, his success slowly grew, and his artists seemed poised for national stardom after a breakthrough performance by Otis Redding at the Monterey International Pop Festival. Tragically, Redding’s life was cut short just a few months after the festival, and Walden found himself without a top artist. Redding was also the de facto leader of the soul and R&B artists that called Macon home, and without his strong presence and guidance, the scene began to struggle. Furthermore, the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. less than half a year after Redding’s death caused a rift between black and white artists working for Southern labels and studios. Suspicion and tension crept into a once-harmonious working environment, and black R&B artists pulled away into an increasingly insular community.

However, before Redding’s death, Phil Walden – along with his brother Alan, Otis and local engineering student Jim Hawkins – had completed the purchase of a building in downtown Macon. The idea was to install a studio that would allow artists associated with Phil Walden’s management group to record high quality demos without the cost associated with outsourcing the work to studios like Stax or FAME. Amid an uncertain future surrounding Redding’s death, a small group of musicians with little to no experience in the business of producing records worked to build the studio from the ground up. The large building was nothing more than a makeshift control room and live room with a homemade board. Jim Hawkins remembers construction going on between takes of songs.

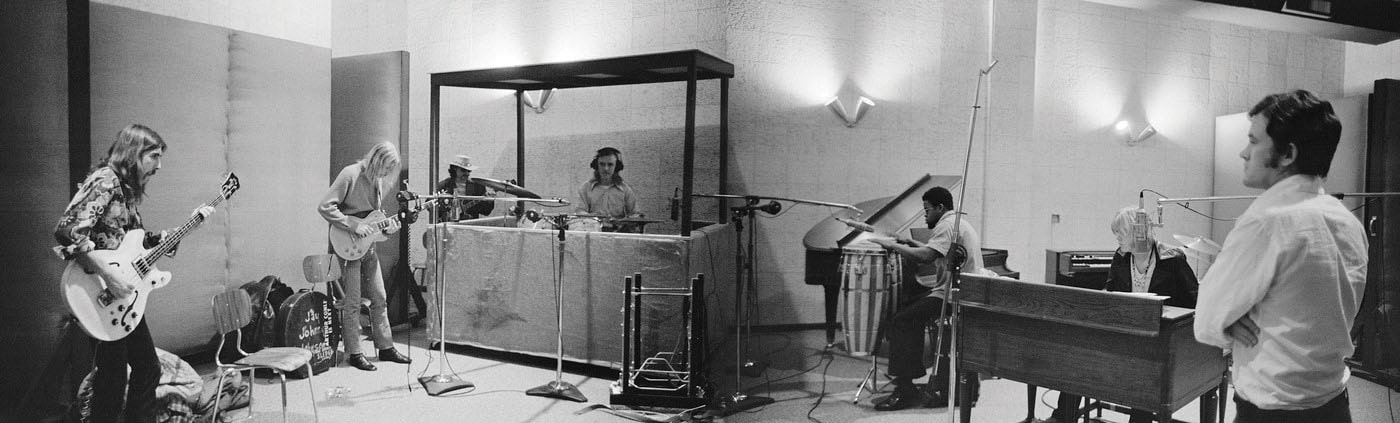

Capricorn Studio (Photo by Herb Kossover)

Gradually Phil Walden’s energies turned to the construction of a record label and the hiring of a studio band to back his artists. One of his first moves was to buy Duane Allman’s contract from Rick Hall at FAME Studios. Although not entirely certain about what to do with the guitarist, Walden took a chance on him after being impressed by the consistency and energy of his studio work, especially on Wilson’ Pickett’s version of “Hey Jude.” Walden also contacted other members of Allman’s former band, the Hour Glass, in an attempt to bring them to Macon and continue to make recordings along the lines of a few tracks they put to tape at FAME as their band was falling apart. Though they didn’t want to get the band back together, Pete Carr, Johnny Sandlin and Paul Hornsby agreed to join Walden in Macon to be a part of his studio house band. As the studio was still being constructed, the three men, along with bassist Robert Popwell, began writing and testing out the new system. A 7” resulting from those sessions, “Pulley Bone” b/w “Ripple Rap,” two sides of heavy, psychedelic takes on MGs-style, in-the-pocket soul, was the first release on the Capricorn label under the unimaginative – yet fitting – moniker, Macon.

As work was progressing on the studio in Macon, Duane Allman was busy gathering together musicians for what would eventually become the Allman Brothers Band. First came Jaimoe on drums, a veteran of bands touring in support of soul greats like Otis Redding and Percy Sledge. Berry Oakley soon followed on bass, and loyalty to his Second Coming bandmate brought in Dickey Betts on guitar. After communal gigs with likeminded Jacksonville band the 31st of February, a second drummer was added by way of Butch Trucks. The fluid group held lengthy rehearsals in Muscle Shoals and Jacksonville with Duane Allman and various other musicians taking vocal duties, but in Allman’s mind, his brother would be the perfect fit for the job. Gregg Allman was still in California fulfilling a recording contract leftover from the Hour Glass days, but with a bit of hardnosed convincing, his big brother was able to convince him to travel to Jacksonville to round out the band, which would soon relocate to Macon and start recording demos in the new Capricorn Sound Studios.

The Allman Brothers Band in Studio (Photo by Baron Wolman)

With the arrival of the Allman Brothers Band, the scene in Macon became an eclectic mix of musical styles. Holdovers from the R&B heyday of Phil Walden and Associates were recording alongside longhaired new arrivals, and Capricorn was also gravitating more toward white blues and singer-songwriter styles, releasing records by Jonathan Edwards, Livingston Taylor, Wet Willie and Cowboy. Members of the Allman Brothers Band also backed Johnny Jenkins for his Ton Ton Macoute, an album at least partially made up of discarded Duane Allman solo sessions from Muscle Shoals. With the arrival of more and more self-contained bands, Walden and Fenter soon realized that the model of a studio band backing solo artists was outdated. Paul Hornsby and Johnny Sandlin put down their instruments for the most part to take on new roles as producers. The two would go on to produce numerous hit records for the label, among them Gregg Allman’s Laid Back and the Marshall Tucker Band’s first, self-titled record.

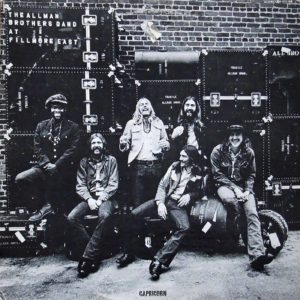

The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East (Photo by Jim Marshall)

Phil Walden and Capricorn Records put nearly all their assets behind the Allman Brothers Band as the label’s flagship band, but success was slow in coming. Tours were relentless and the money was tight. It wasn’t until the success of their live album, At Fillmore East, that the band started seeing a decent amount of success. Despite the tragic loss of Duane Allman and Berry Oakley to motorcycle accidents only a year apart, the band persisted, and by 1973, they were one of the biggest bands in the country behind the overwhelming success of Brothers and Sisters. Capricorn – and the city of Macon – rose in popularity behind the band. Suddenly, Southern was hip, and Macon was flooded with artists and onlookers eager to join the scene. With record distribution duties newly being handled by Warner Brothers, the independent Capricorn label enjoyed creative freedom to release music that represented the South, proving that the music business could survive in a laid back setting far from the harsh environments of New York City or Los Angeles. Nothing represented this new-found popularity better than the Capricorn Barbecue and Summer Games, an annual throw-down held at Lakeside Park, just outside the Macon city limits. The event featured Capricorn acts and drew guests as diverse as Lester Bangs, Andy Warhol and Jimmy Carter, who was destined for the White House in 1976 thanks to a little help from his friends down South.

Jimmy Carter at the Capricorn Barbecue and Summer Games (Photo by Herb Kossover)

However, by the end of the 1970s, Capricorn had lost its two biggest names, the Allman Brothers Band and the Marshall Tucker Band – one to an inevitable breakup after the loss of two founding members and the other to a more lucrative offer from a larger label. Punk and disco were turning the nation’s ears away from the South; good ol’ boy and label friend Jimmy Carter was out of the White House, blamed for an economic recession that had swept across the country. In short, the good times of the ‘70s came to an end, and Capricorn went with them, finally declaring bankruptcy in 1980 after the collapse of a joint venture with Warner Brothers.

In the whirlwind of its decade-long existence, the label left behind an impressive legacy. For an independent record label, Capricorn released an eclectic array of records that more often than not defied genre lines and undeniably extended beyond the boundaries of the “Southern Rock” moniker. Decades after the label’s quick and fatal fallout, Capricorn’s influence can be found all over today’s musical spectrum: from the funky prog of the jamband scene to the overdriven outlaw-ism of modern country music.

In a fitting coda to the unlikely success story of the label, Phil Walden would revive the Capricorn name in the 1990s like he had never missed a beat. The first signee, Widespread Panic, would return the label to relevance, and with the help of his son and daughter, Phillip Jr. and Amantha, the label would break into the alt-rock scene with acts like 311 and Cake.